Lost but Not Forgotten to History

Before there were stat programs, media guides, and web sites, at lot of college sports history was kept pencil to paper. As a university grows, that can make it hard to keep history straight. That’s the case with Lindell Bradley, who was recruited to play baseball at South Carolina in 1967, which made him the first black varsity athlete in any sport at the school. Unfortunately, Bradley’s place in Gamecock history fell through the cracks … until now.

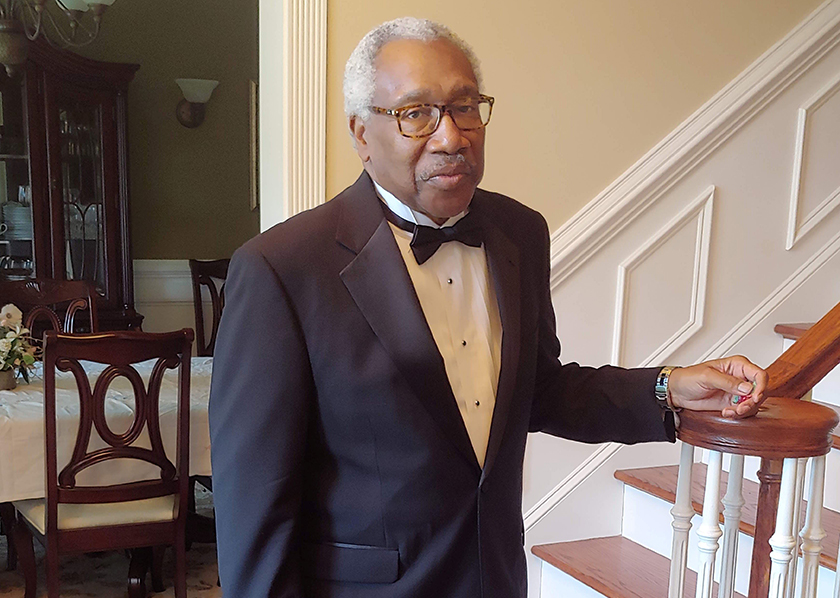

“There is good and bad in everything, and you have to work to find the good,” said Bradley who lives in Ocean Isle Beach, North Carolina. “Sometimes the good does not appear. I had some bad experiences, but I also had some extremely important, good experiences at Carolina. Had I not had some of those experiences, I would not have learned how to cope with situations that were beyond my comprehension or beyond my abilities. I would not have known how to stay calm and talk. Those things were all taught to me through my college experience. I appreciate what I learned while I was there.”

“Lindell Bradley represents a very important part of our Athletics Department’s and our University’s history,” said Athletics Director Ray Tanner. “We are grateful that he was able to share the story of his experiences here so that they are not lost to history. Lindell is a true pioneer who proudly wore the Garnet and Black uniform during a transformative time in our country, and his courage helped pave the way for many others to follow. We are excited to have him back on campus this weekend so he can be properly recognized by the University and Gamecock Nation.”

It’s been more than six decades since Henrie D. Monteith, Robert Anderson and James Solomon became the first black students to enroll at the University in the 20th century. A few years later, individuals such as Carlton Haywood (football, 1969), Casey Manning (basketball, 1969), and Jackie Brown (recruited for baseball in 1969 but switched to football in 1970 and also played basketball) became pioneers and had long been recognized as the first black student-athletes in their respective sports, until recently. By then Bradley was no longer playing baseball as he focused on earning his engineering degree, which was another tremendous accomplishment.

“For us to be at the University was an event itself,” said Bradley’s wife, Linda. The couple met while students at South Carolina and have been married for 51 years. “I got there a year after him, and there were only around 200 black students on the whole campus. We weren’t focused on being the first this or that. We were focused on surviving and trying to succeed and prove that we had a reason and a right to be there. We were more concerned about showing that we deserved to be there.”

“And staying there!” said Bradley. “There was a professor who said to me, ‘I don’t know why you’re working so hard. I’ve never had a black student pass my class, ever.’ I said hmm. It looks like I have a challenge! And he laughed!”

Bradley attended Butler High School, which was then an all-black school in Hartsville, South Carolina. During his senior year in the spring of 1967, he helped his team win a state championship and that opened some doors for his future.

“I had a very good series pitching and hit two homeruns in a three-game series,” said Bradley, who also played third base and shortstop. “A Major League (Baseball) scout was watching the game and asked if I had considered playing baseball at the next level. I obviously was excited and gave him a very strong affirmative response of my interest. He said he would have to speak with my parents since I was under 18 to discuss the matter any further.

“When meeting with my parents, he indicated that my assignment would likely be on the west coast and that I would begin during the coming summer. As my parents were both teachers, they expressed their interest in my going to college and maybe I could play baseball while going to college. I asked if he could arrange for a tryout at USC, which he did, and the school contacted me with a schedule on when to come to the campus for a tryout.”

During this time, student-athletes were required to have a minimum SAT score of 800 to receive any sort of financial aid, and despite many segregated black high schools not having the same instructional levels and resources as the other schools, Bradley met the criteria. His wife credits the nuns from his Catholic elementary school for instilling discipline and knowledge in him early on. The South Carolina baseball program was under the direction of Coach Jack Powers. Tryouts went well, and he became a member of the freshman team at South Carolina during the 1967-68 school year.

“He (Powers) was very adamant about it,” Bradley recalled. “He said he liked my personality and the way I went after things. He gave me the impression that he understood what I would be going through, but in a lot of situations, I don’t think he completely understood.”

An integrated campus was still a relatively new thing at this time, and Bradley said his presence on the baseball team was met with mixed reviews.

“Yes, I was scared,” Bradley said of his decision to come to South Carolina. “I had no idea what to expect. It was my first time living away from home.

“The coaches were very open and supportive to my being on the team. However, they missed a lot of sensitivity of how to handle my being on the team as some team members were not happy with my being there and showed it on several occasions during practices and during travel to road games. There were two team members from the freshman team that agreed to room and eat with me during road trips and that made my being there a lot easier. Those guys were great. They were Christian athletes.”

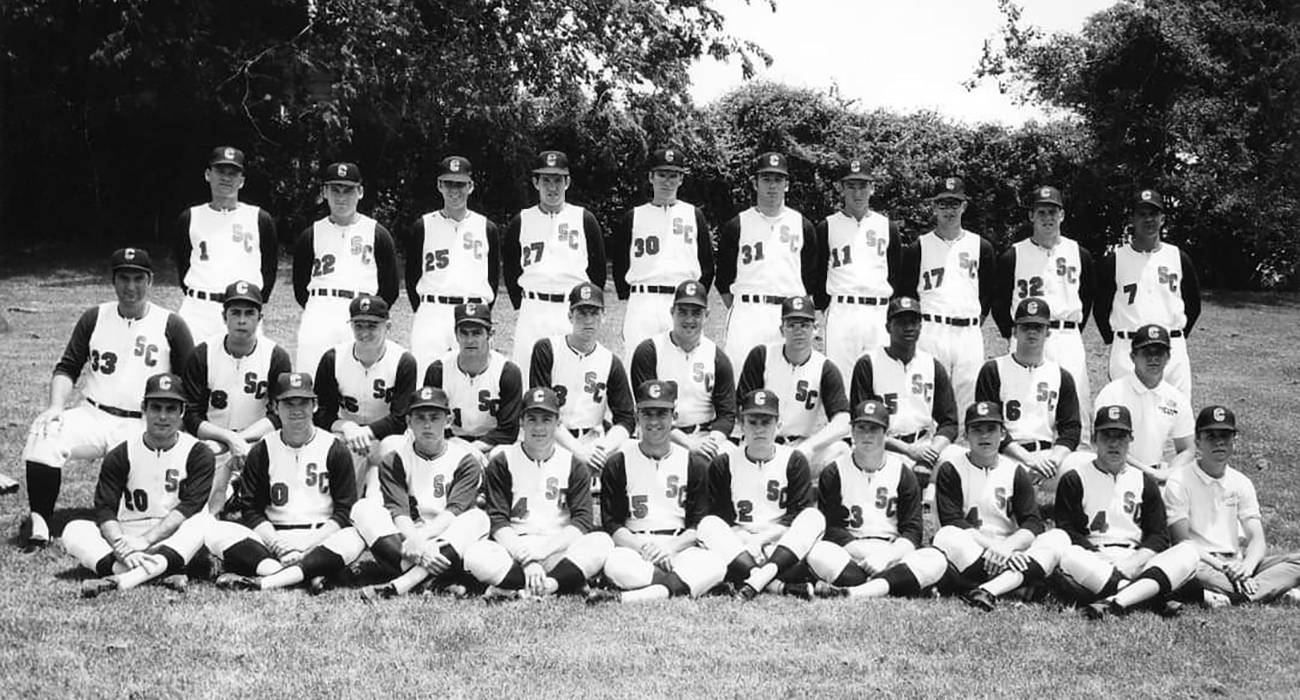

1969 South Carolina Varsity Baseball Team

#35 Lindell Bradley (middle row, third from right), #16 Joseph Land (middle row, second from right), #23 Tommy Jones (bottom row, fourth from right), #14 Wallie Jones, fourth from left)

“Even though it was not full of highlights, I was very proud to have this great opportunity to play as a Gamecock.”

Some of his teammates said they may not have been fully aware of all that Bradley was going through.

“I thought he blended in well,” said Wallie Jones, who was a senior middle infielder when Bradley played on the varsity in 1969. “I was married at the time and didn’t live in the Athletics dorms, so I wasn’t around the guys a lot off the field. I thought he was a likeable guy. I never saw him pouting or complaining about not playing much. I didn’t know him very well away from the ballfield. I felt like he was treated like the rest of us on the team from the coaches, but I wasn’t in his shoes.”

“I’m sure he had to feel a lot more pressure,” said Tommy Jones (1969, 1970), brother of Wallie and a fellow teammate. “What stands out to me was that he had such class. He handled those pressures. I know he heard some things that probably were not right. Those were volatile times. I don’t suggest that I handled it very well.

“We had long bus rides. I sat by him sometimes. He would pick up his books and study on road trips. That was unheard of with our group! I admire the guy. He was there for an education. He knew that he would be the first black guy here (for sports). He would carry food on the bus that was from his parents. He would offer some of it to me. We got a stipend for food, but it wasn’t a lot. I do remember thinking this guy would be a politician because he was never confrontational. He was under a spotlight in a way. He did a magnificent job of navigating all of that. I never heard him complain.”

“He was a great teammate,” said Joseph Land (1968-1970), who was a former pitcher and later a catcher, as well as team captain for the Gamecocks as a senior. “He had that winsome personality. He was a terrific athlete. He was fast. He had all the skill sets. He could run, and he could hit. He was kind of the Jackie Robinson of our team.

“It was a different time. I’m sure he had to go through some things that we didn’t have to go through. As teammates, I didn’t see him any differently than anybody else because the guy could play. I was glad to have him.”

Bradley noted that fan reaction at games was mixed as well.

“There were a number of instances where threats were made and negative cheers made off the field,” Bradley said. “There was never an incident on Carolina’s field but there was an ‘N’ word yelled out at a Georgia Southern game.

“The next year, we went to a restaurant one time in Georgia and the waiter came over and told me that I couldn’t eat there. Coach said, ‘sorry Linny.’ He gave us fifty bucks and told us to meet them back at the hotel. So, me and my two buddies found another place to eat and went back to the hotel.”

Bradley played on the varsity team in the spring of 1969, and although he didn’t play much, he wasn’t discouraged.

“I was quite proud of my accomplishment just to make the team and contribute in any way that I could,” Bradley said. “During my first varsity year, there were only two times where I appeared in a game. There were a number of games where I was inserted in the games late as a defensive move, but no record was recorded of those appearances. Even though it was not full of highlights, I was very proud to have this great opportunity to play as a Gamecock.”

Carolina baseball didn’t have the facilities nor the huge fan base that the program enjoys now.

“We might have had a couple hundred people at the most at our games,” Bradley said. “The focus was on football and basketball in those days.”

Bradley was excelling in the classroom as he studied engineering, but conflicts with classes and his athletics schedule, in addition to difficulty in getting to and from games and practices, which were held at the old Sarge Frye Field as well as Capital City Stadium off campus, forced him to make a decision.

“I did not have transportation in order to get to morning classes back on campus,” Bradley said. “We had practice twice a day before the season started, so I had to arrange my classes around practice. I would get to my classes just by my desire to get there because I had to walk. My classmates used to just drive on past me. There wasn’t the campus transportation back then.

“I met with the coaches and the Engineering Dean to resolve the conflict but was unable to solve the problem (without changing his major). The engineering department offered me a work study assignment to make up for the lost scholarship, and I decided since the engineering school was trying to help me that this might be the best solution. So, during midyear 1970, I left the team and finished my degree with the help of work study and summer work. I chose education over athletics. This worked out to be the best solution for all.”

After graduating from South Carolina in 1972, Bradley accepted a job as a project engineer with Mobil Oil Corporation out of Philadelphia. He worked in a number of technical assignments with Mobil and with Exxon after it merged with Mobil in 1999 for 35 years.

“My career was exciting and provided me the opportunity to travel to more than 60 countries and a variety of cultures in Europe, Africa, Asia, Middle East and South America,” Bradley said. “The same lessons that I learned in college, I took those right into my work. The amount of risk taking, and the ability to discuss things and come up with solutions helped me in my career, which eventually got me up to an executive level.

“I was a member of the Society of Civil Engineers and the American Petroleum Institute. Other activities included serving with Alpha Phi Alpha in providing community services in the Washington D.C. area. I also served as an inaugural member of the Black Engineer of the Year Award and Recognition Program in Baltimore, Maryland.”

Bradley continues to be involved in his community through his work with The First Tee of the Coastal Carolinas and Seaside United Methodist Church.

Lindell Bradley’s baseball career as a Gamecock is not over, however. He will be at Founders Park to throw out the first pitch for South Carolina’s game against Kentucky on Sunday, April 28.

Now retired, Lindell and Linda have three children and six grandchildren.

PHOTOS (L-R): 1.) Lindell and Linda with their children James, Karen, and Linny. 2.) Linda and Lindell with grandkids Dillon, Cameron, & Jackson. 3.) Daughter Karen with husband Lewis and Bradley’s granddaughter Lauren. 4.) Grandson James. 5.) Granddaughter Brianna. 6.) Lindell Bradley